Working from Home: Lessons Learned from Working in Space

As we begin the third year of the pandemic, I’ve entered a sort of twilight zone. Although my office has reopened, much of my work involves hours of computer time and Zoom meetings, so I’ve often found it difficult to motivate myself to commute and sit masked in my open office when I could work from the comfort of my apartment, with all the accompanying tea, snacks, and cozy blankets. I made a significant effort throughout the pandemic to establish a routine and comfortable work station, and as a result, I’m now finding it hard to leave the conveniences of my home office.

I’ve also been reading Out of This World: The New Field of Space Architecture by A. Scott Howe and Brent Sherwood, which has got me thinking (once again) about how many of the lessons learned from longterm spaceflight and astronaut psychology are more relevant than ever. While I may have gotten used to the WFH life, much like human spaceflight, it was not without significant rounds of trial and error.

So here are seven lessons learned from living and working in space that I’ve found relevant to my regular life here on Earth.

1. Routine vs. over-scheduling

Scheduling and routines have their merits. Personally, I have found routines to be invaluable in grad school, not just while juggling multiple commitments, but also for maintaining a general sense of sanity. However, there is a risk of over-scheduling yourself, especially while working from home. In the past two years, the divisions between work and life have begun to blur with work that is increasingly digital and subsequently more accessible than ever. I’ve found that I need true, unscheduled down time - a point I’ll get to later - and having back-to-back commitments designed to maximize productivity leaves me feeling empty, exhausted, and burnt out. It turns out that over-scheduling isn’t just a problem here on Earth; it’s a very, very common for astronauts working in space.

Astronauts onboard the ISS are busy. They are highly trained experts and only in space for a limited time, so their time is incredibly valuable. However, astronauts onboard the Station only recently achieved what could be called an efficient work day. Previously their days were filled with a variety of unforeseen tasks, including unexpected maintenance, diagnostics, and repairs that took up 1.9-2.4 hrs/CM/day (hours per crew member per day). This extra maintenance (usually caused by the Environment Control and Life Support Systems, which are critical and cannot be ignored) fell on top of the crew’s already busy schedules, and would sometimes eat into personal downtime and sleep.

As the ISS has aged, the number of maintenance hours has fluctuated due to additional ground/crew knowledge of its systems and increasing likelihood of part failure over the component lifespan. But after over twenty years, the average day onboard the ISS looks something like this:

Meeting with Mission Control - 2 hrs

Workday - 12 hrs, and of that:

Primary Mission Tasks (research, operations, maintenance) - 6.5 hrs

Physical Training - 2.5 hrs

Other (preparation for primary tasks, unplanned repairs, general upkeep) - 3 hrs

Finalize Tasks (pre-dinner) - 1 hr

Sleep and Personal Time - 9 hrs

I was surprised by the amount of time dedicated to meetings, repairs, and task finalization when compared to research and personal time. In particular, the 2 hr meeting with ground seemed excessive until I learned about the vital role that ground support plays in all crew scheduling, operations, diagnostics, and science activities.

In the bioastronautics community, there is a lot of conversation about the relationship between ground and crew. Command hierarchy is critical in spaceflight, and there is certainly a psychological weirdness about differing to a group of people in a cozy office 400 km below to make decision that affect your daily life and safety when you are flying around the planet at 17,000 mph. There has been occasional tension between crewmembers and ground support, particularly when it comes to schedules and workload.

An urban legend surrounding the Skylab mission claims that the crew formed a mutiny due to their overly-packed schedules. While the myth of the astronaut strike has been rebuked, there were real discussions between the crew and ground support surrounding crew work demands. These discussions were especially heated on Skylab, which was a notably unpleasant place to live due to its runaway thermal control, noise, unreliable parts, and gas in the water supply that contributed to crew flatulence. Skylab astronauts expected an average of 0.75 hr/CM/d of maintenance, but instead had to contend with 4 hrs/CM/d of unplanned maintenance onboard the habitat. This unplanned maintenance fell on top of the crew’s planned maintenance, upkeep, and science work, and dramatically ate into crew down time. However, productive discussions with ground support ultimately resulted in a reconsideration of crew scheduling and a dramatic increase in crew effectiveness and performance. (Turns out, if you aren’t over-scheduled, you can be more happy and productive. Who knew?)

And so I’ve learned to avoid back-to-back scheduling, and have begun to reconsider what tasks used to go into my workday: commuting, talking with lab mates in the hallway, lunches, planning for my week. I’ve made a point to make sure these get baked into my WFH days and to avoid trying to hit 8-10 hours of nonstop grind (with varying success). I’ve often found that those 8-10 hours of nonstop work are not the most productive means to the end, and there’s a good reason I didn’t achieve it before WFH became a fact of life.

(This lesson took me the longest to learn. So long, in fact, that I am arguably still learning it.)

2. Zoning

Zoning is an obvious part of architectural and urban planning design, but is often overlooked in space habitats. This is partly due to the fact that space habitat designers are engineers and not trained architects, but mostly due to the limits that space poses on habitable volume. Most habitat spaces have to be multi-use out of necessity. However, it is still important (especially as missions approach a duration of months to years) to have separate areas for work, sleep, and relaxation. This is accomplished in modern space habitats by sequestering activities to different modules. The lab space and work areas are co-located, and the crew quarters are private, phone booth-esque bunks where the astronauts can go to sleep or converse with family and friends on the ground. The exercise equipment is separate from the living space, and meal prep is located in a communal area. While some of these areas overlap in practice, there’s an effort to divide it due to practicality (i.e. have better air filtration near the exercise equipment) and astronaut sanity.

While working from home, it is easy to work from the couch, the kitchen table, the bed, or the floor. Is it productive? No. Is it ergonomic? No. Does it make me feel good when I ‘stop work’ for the day and close my laptop, just to sit back down on the couch? Absolutely not. I learned pretty fast that I needed a way to divide out my day by location and activity. This isn’t to say that I always work from my desk and never do work from the kitchen counter or the couch; I just know that if I want to have a productive workflow or take a serious meeting, I have a place to do that. It also helps ‘turn off’ in the evening when I know that other areas (the couch, my bed) are not places where I should be thinking about work.

A picture from inside one of the ISS crew quarters, with sleeping bag, computers, and personal items attached to the wall via velcro.

(Imaged credit: NASA)

3. Personalization

Like zoning, personalization is something that may seem trivial at first, but is actually incredibly important for long-term physiological and psychological health. I tend to think of design personalization in two main categories: ergonomics and expression.

I spent the first ~6 months of the pandemic working at a kitchen counter on a $30 Ikea stool, and my lower back ultimately paid the price. Eventually, piece by piece, I moved on to a desk, and made it somewhere where I could actually work productively: first by investing in an ergonomic gaming chair, and then by finding a widescreen monitor I could hook up to my laptop. Personalization goes beyond workspace comfort though - I’m a firm believer that personalizing your living space can boost overall happiness, productivity, and sense of calm. While I can definitively say that my splurge on an ergonomic gaming chair was 100% worth it for my home office, I will also argue that the paintings, posters, string lights, and tiny plants that I added to my desk were just as effective in boosting my desire to exist in that space.

In space, personalization becomes a challenge of design and statistics. The crew of the ISS is international, and subsequently involves a large variety of demographics and physiological differences. The crew quarters onboard the ISS were designed through extensive ground mockup testing and lessons learned through the Skylab, Mir, and Space Shuttle programs, and the considerations for their design included the physical dimensions of a wide variety of people, including very short women and exceedingly tall men.

You may have heard of the recent controversy surrounding the lack of ‘small’ EVA suits that would fit women astronauts during the first ‘all-female spacewalk.’ While it’s easy to pick up the torches and shake your fist at all those sexist designers at NASA, spacesuits are also incredibly expensive, and by necessity need to be designed for as large of a population as possible, much like cars and aircraft. This inherently results in a whole host of challenges and can ultimately result in a ‘one size fits no one’ compromise. Ill-fitting space suits are a particularly egregious example that affects all users, and have resulted in shoulder strains, ankle problems, blisters, and dangerous situations for the astronauts. This isn’t meant to let NASA off the hook, rather to illustrate all of the considerations that go into a complex design such as an EVA suit.

However, there have been far more successful instances of designing for personalization onboard the ISS. In the crew quarters, velcro space on the walls allows the crew to store personal effects and decorations. Work spaces can be adjusted for height or personal preference. Other retrofitted improvements, such as hand- and foot-holds that can be rotated and maneuvered according to each astronaut’s preference, have been proposed for the crew quarters. It is, after all, a home.

Impacts of microgravity on ergonomics - beyond personalization, designers have to take the effects of microgravity into account when designing orbital habitats. (Image credit: Bahadori et. al, 2012)

Behold, the chaos!

(Imaged credit: NASA)

4. Privacy

“In space, no one can hear you scream.” While this may be true in the vacuum of space, it turns out that inside the ISS, everyone can hear you, all of the time. They can also hear all of the various beeps, hums, vibrations, clicks, and other noises made by the machines, alarms, and experiments that exist inside the Station. Keeping noise out of specific locations is incredibly difficult. Engineers have to reconsider everything from fans to pumps to treadmills, and take that extra noise into account through the design process due to the space and structural limits of the ISS. In some cases, low-level alarms are designed to specifically not go off in places like crew quarters to try to give the off-duty crew extra rest time. (In this scenario, the on-duty crew decides if it’s worth alerting the sleeping crew.)

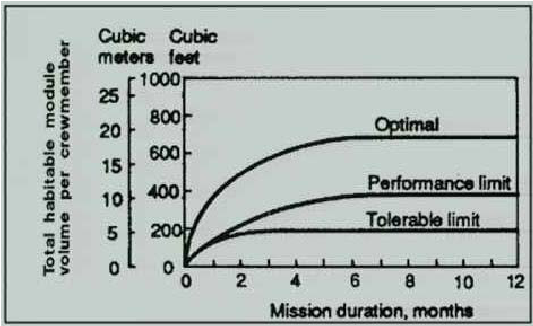

There’s also the more immediate consideration of space. Physical space. Mass - and subsequently volume - is directly correlated to cost in space, and so unfortunately, we cannot design space stations to be infinitely large. However, there are scientific guidelines to how large the habitable space onboard should be, and this relationship is illustrated in what is known as the Celentano curve:

The Celentano curve, which represents the relationship between habitable volume, performance, and mission duration.

The idea of the curve can be thought of in Earth analogies. You can go camping with your buddies for a weekend and live comfortably inside a tent together. However, here on Earth you have the luxury of being able to leave the tent. You probably would not want to live with three of your friends all together inside the tent for weeks on end without leaving. During the early lockdowns of the pandemic, many people found that they were forced to coexist with their families, roommates, and partners in spaces that suddenly felt too small when everyone was home all the time, trying to live their respect lives. This all illustrates the main point of the curve: the more people, the longer the stay, the more required habitable volume. This is particularly important when going from hours -> days, and days -> weeks, but the curve begins to flatten out after several months.

My partner and I started the pandemic in a one bedroom apartment that was basically half a wall away from being a large studio. The apartment served us well through the firs two years of grad school, but when we both started working from home, we found that having two rooms to work, cook, work out, sleep, relax, and exist together was more difficult now that the two of us were trying to take zoom calls in the same 200 square feet. We had been considering moving to a larger space before the pandemic, and that summer we upgraded to a space with far more living area, an office, and extra storage space. I’m very grateful we were able to upgrade, as it made WFH that much more bearable in the long haul.

5. Regular exercise

The psychological and physiological benefits of regular exercise are well established. But in space, exercise is even more critical for long-term astronaut health, as it can help prevent and slow the muscle atrophy, bone density loss, and heart deconditioning that comes with spaceflight.

Exercise is an important part of my daily routine, and is a time that I treat as stress relief, meditation, and time to connect with nature. I used to be content to go to the gym and work out on treadmills or with machines a lot of the time, but during the pandemic, I’ve tried to use exercise as an excuse to get fresh air and sunlight. For me, working out became a chance to unplug and leave the space that I had been spending the other 14 hours of my day.

Unfortunately, astronauts do not have the luxury of getting out into nature during their workouts. Because of its importance for long-term health in microgravity, regular exercise is regarded as part of the astronaut’s job, and often involves taking measurements or running experiments during their sessions. Additionally, astronauts face limited workout options onboard the ISS: a large apparatus for resistance training, a treadmill named after Stephen Colbert, and a cycle ergometer. Despite the lack of variety, astronauts have made the most of their exercise time in space. In 2006, Sunita Williams ran the Boston Marathon from space in 4 hrs, 23 minutes, and in 2016, Tim Peaks ran the London Marathon in 3 hrs, 35 minutes onboard the ISS treadmill.

Sunita running on the ISS treadmill.

(Imaged credit: NASA)

A very happy Patriot’s Day.

(Imaged credit: NASA)

6. Lighting and windows

At the risk of sounding like a cringe-worthy millennial Target decoration, humans are like houseplants. We require food, water, air, and natural light in order to meet all of our physiological and psychological needs. But in space, windows are a novelty; they’re heavy, difficult to pressurize safely, and can let in a whole host of fun radiation. However, they are crucially important to astronaut mental health, and can help prevent feelings of claustrophobia (feeling like ‘spam in a can’). They also can provide the overview effect - a sense of awe, respect, and appreciation for the fragility of Earth that comes from flying high above it in space.

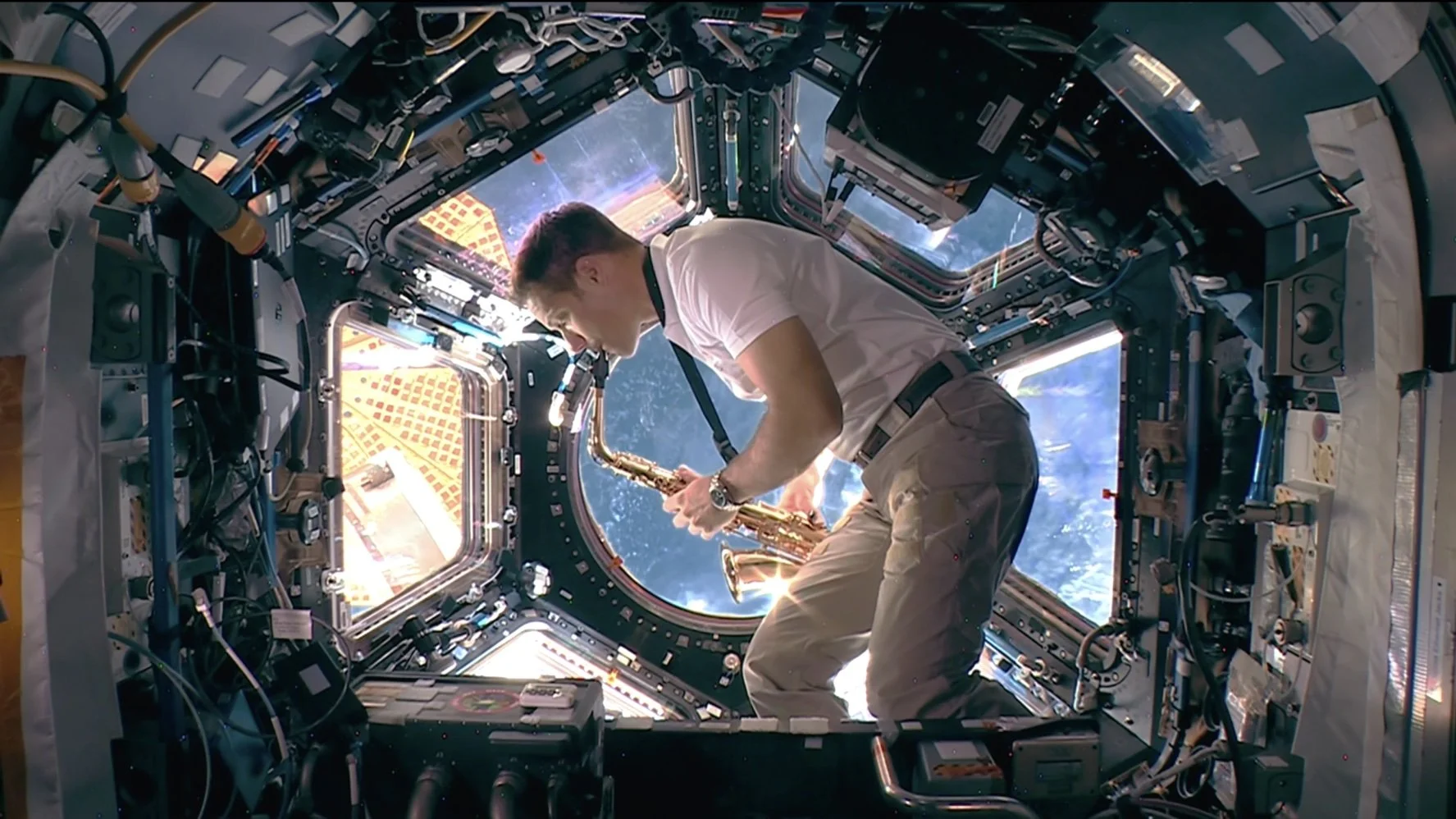

Lighting onboard the ISS is a different story. Unfortunately, the majority of the Station is still fundamentally a laboratory space, and the lighting is what you would expect: harsh overhead LEDs that hum, buzz, and flicker across crowded white walls. However, the ISS also has the cupola: a small hexagonal bubble sticking out from one module where astronauts can go to relax, take photos, or stare down at the Earth below. Many astronauts have claimed that this spot is their favorite part of the International Space Station.

But lighting has multiple uses in space. Due to the microgravity environment, it can be difficult to discern orientation or location within the Station, and lights can help orient astronauts and indicate which direction they should go to any given location. Windows have long been used for teleoperation of robotic arms and cargo resupply spacecraft as a line of sight for the operator.

While I’m not regularly attempting to pilot a robotic arm from my desk, in my own personal experience, I’ve found that the lighting of my work and living spaces plays a huge role in my happiness. I love natural and warm-leaning lights; I’m a sucker for faerie lights, Edison bulbs, candles, and all manners of cozy household additions. I love working by windows and outside on my balcony when I can.

(Imaged credit: NASA)

7. Down time

This final lesson is related to the first, but I believe it’s important enough for a solo mention.

When I first returned to the office, I discovered some of the shortcomings of my over-scheduled routine: I would be taking calls en route to lab and staying late in the building to make sure I was on time for my 6pm meeting. After stopping in the hallway to talk to my advisor or breaking for lunch, I would feel incredibly anxious; my mind would mentally tally up all the time I had ‘wasted’ and demand that I make it up somewhere else, either through a 14 hour workday the next day or working through all of my meals the rest of the week. I had un-engineered commuting, lunch breaks, and normal office conversations out of my daily routine. And while I still enjoy working from home to regain some of the productivity I lose in the office, I believe that these interactions and forced down time are actually incredibly important to avoid burnout. They also ensure that we don’t work in a vacuum: that hallway conversation with your advisor incubates an idea or formalizes a thought you had, and that lunch break with your lab mates gives you a chance to decompress, vent, and have some laughs.

An old coach of mine used to stress the importance of ‘stare at the wall’ time - time that wasn’t productive, scheduled, or a chore. She reiterated again and again that even though you can volunteer or monetize or play a sport in your free time, you still need down time - time that is wholly and completely unstructured, to waste without guilt or sacrifice. This can often be done through consuming media, like watching TV or reading, or through socializing with people you love. The importance here is that it is intentional and guilt-free.

Some of my favorite instances of down time in space include astronaut photography, music, and the ISS Olympics - but relaxing on Station isn’t necessarily something filmed or produced. Calling home, watching TV, or talking with your crew over a meal are all equally important in relaxing at the end of a long day.

Living in adverse conditions - whether it be in a floating pressurized tube high above the Earth or a global pandemic - takes a toll over time, and its important to be able to adjust as your needs and situations change. Although working a white-collar job from home is very different from the role of an astronaut and a privilege in and of itself, I hope that some of these lessons learned from spaceflight can improve your day-to-day routines and make everything a little more manageable.